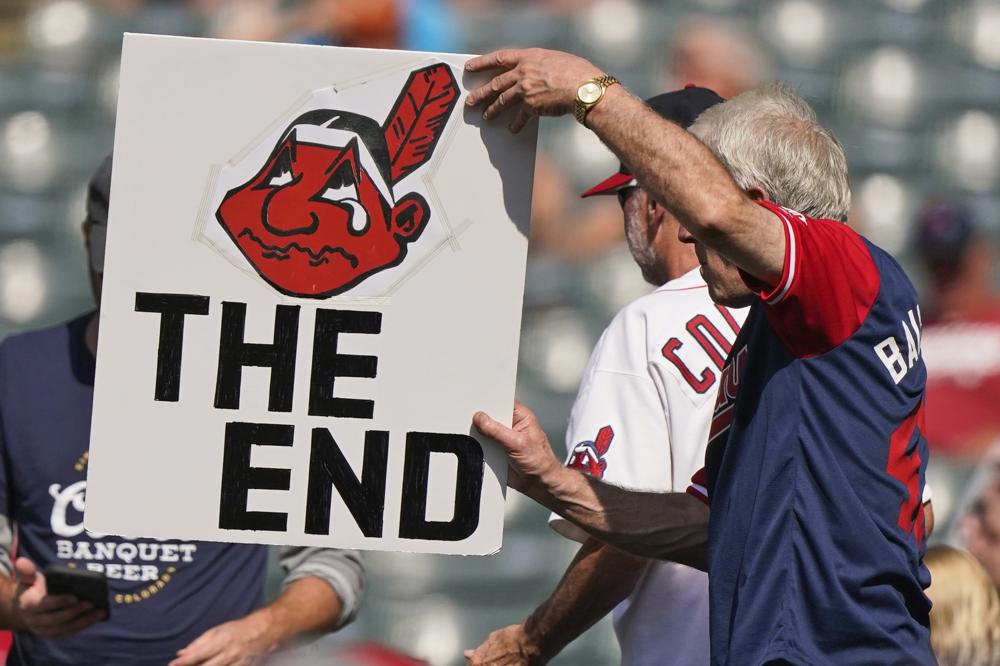

So Long, Tribe

This tidy simplification leaves unresolved the question of why Sockalexis’ “Indian” heritage was evoked as a nickname for the Cleveland Spiders—was it out of disdain for him, or in celebration of his remarkable skill as an outfielder and as a hitter, or a confounding mixture of attitudes and beliefs that were characteristic of the time?